Rugs made from strips of cloth existed well before factories began producing cheap fabric, but not in anything like the same quantity. Even in quite poor households, rag bags of the 1800s were filling up with old clothes and scraps left over from dress-making. In the factories, there were clippings and oddments to be sold off cheaply or swept up by employees. Cotton feedsacks gradually became available too. Rag rugs created from scraps on a woven background (the second and last kinds in the list below) could use old jute sacking or cheap burlap as a foundation. These materials were easily available in many parts of North America and Europe by the middle of the 19th century. With time, and a little skill, families could warm and decorate their floors.

By 1900, some rag rugs were less about thrift, and more about craft. There was a movement towards careful design, and more elaborate techniques, and craftswomen started to buy and/or dye fabric with particular patterns in mind. This interest in rug-making as an aesthetic craft was stronger in the US than in the UK, where rag rugs were mainly seen as an economical choice for poorer homes until the mid-20th century. While Britain tended to dismiss rag rugs as “working-class”, American county fairs and exhibitions offered prizes for rag rugs alongside patchwork quilts and other textile arts.

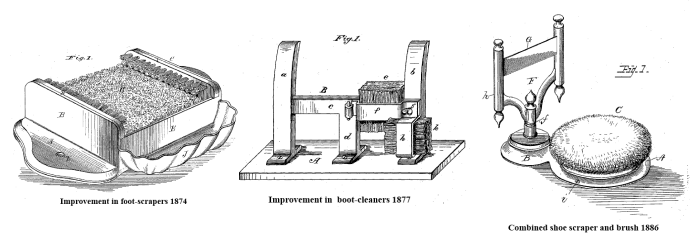

There are many varied ways of making cloth remnants or “rags” into floor coverings, but this is a brief outline of the types known in the Victorian era.

- Rugs woven on a loom: perhaps a linen warp thread with wool or linen strips used for the weft. These are probably the oldest kind. “List carpets” in 18th century England and colonial America were one of the cheapest kinds of soft floor covering. Sometimes woven lengths were sewn together to create rag carpeting.

- Rugs made with cloth scraps looped through a loosely-woven canvas or burlap background. The rags can be hooked through from the upper side or poked through from underneath, creating varying surface textures from smooth to tufted. Implements for hooking or prodding ranged from home-made wooden pegs to factory-manufactured latch-hooks.

- Rugs made by coiling joined-up lengths of rag. The coils of braided rugs, or mats made from fabric-covered cord were fastened with thread stitching or binding; crocheted versions need no sewing.

- Knitted or crocheted rugs made in one flat piece.

- Rugs, often small door-mats, made by stitching scraps onto backing material. Tongue mat is one name for these, based on the tongue-shaped pieces used in one popular design.

Note: The UK had a large number of different regional names for the rugs in the second category, like clootie, proggy, proddy, clippy, stobbie or peggie rugs or mats. These now seem very attractive, admired for craft, design, and nostalgia reasons, but they were not appreciated by the wealthier classes in the 19th century.

Photos

Photographers credited in captions. Links to originals here:

loom rug, coiled rug, crocheted rectangular rug. More picture info here