A hundred years ago could anyone imagine that darning tools would now be unrecognisable except to antiques or crafts enthusiasts? There always used to be a steady supply of darning in the family mending bag. A woman sitting darning was a common sight, and so was a darning egg. Inside a stocking or sock with a hole in, the “egg” or darner made it easier to stitch a neat repair: not too tight, not too slack.

The simplest old darners are rounded pieces of hardwood – boxwood, maple, apple, elm – with a lovely smooth surface. Edward Pinto, the treen expert, thought the egg was the oldest shape in common use. They were also called darning balls.

Other names and other shapes include darning mushrooms, darners, lasts and wooden “gourds”. Real gourds or cowrie shells could be used, and special 19th century darners might be coloured glass, pottery, or ivory, or have silver handles.*

Darning eggs that open to reveal neatly-stowed sewing accessories are attractive pieces of treen (woodware), appealing to collectors who would never actually use them. There’s something about a clever design with small things unexpectedly tucked inside a well-crafted piece of hardwood. (See pictures near the bottom of the page.) Desirable antiques now, these used to be bought as gifts. Hollow olivewood eggs with needle and thimble inside were exported to England from Southern Europe. You may also come across darners with a detachable handle doubling as a needle case.

In France, every village woodturner had his own style of egg, as you see in this well-illustrated post, and it was once a common present for a bride. Handles were less common than in the UK or USA.

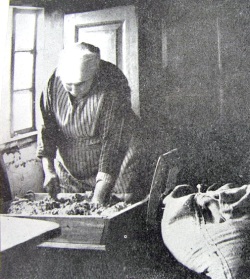

A darning-egg or ball, held in the left hand, is slipped under the hole, with the stocking stretched smoothly, but not tightly, over it.

The Dressmaker, 1916

Glove Darners

When a glove needed darning, little darning eggs were pushed into the fingers. Some glove darners had different-sized balls on each end of a handle. With big sock darners, the handle itself could sometimes be used for glove repairs. Not all glove darners had a handle. Some were simple egg shapes dropped into the finger. The handle-free type was usual in France, as with the sock darning eggs.

All these curved darners were best suited to mending small pieces of knitted clothing. They were not meant to be used for “flat darning” of woven cloth.

*See Old-Time Tools & Toys of Needlework by Gertrude Whiting. Pinto’s Treen and other Wooden Bygones: an Encyclopaedia and Social History

and Thompson’s Sewing Tools And Trinkets: Collector’s Identification & Value Guide, Vol. 2

are other sources of information.

Pictures

Photographers credited in captions. Links to originals here: striped sock, mushroom, painted mushroom, painted eggs. More picture info here

//

http://pagead2.googlesyndication.com/pagead/show_ads.js