Chinese porcelain seemed fine, white and desirable to 18th century Europe, and it inspired skilled potters there to develop their own versions of porcelain. Others worked on more affordable earthenware, trying various clay and flint blends in the search for pale, creamy colours. This new creamware was developed during the mid-1700s.

One of the most successful versions of creamware came from the well-known English potter Josiah Wedgwood who managed to make paler earthenware than anyone else in the 1760s. Part of his success depended on clay from south-west England. Also important were his design expertise and the clear glaze.

After Queen Charlotte ordered a cream table service from Wedgwood he “branded” his cream pottery by calling it Queen’s ware, and didn’t use the name creamware himself. So Queen’s ware, or queensware, is a kind of creamware, but not all creamware is queensware.

Although there were other potteries making creamware, and other people also made crucial discoveries, Wedgwood got the acclaim for being the first to make a high quality pale cream earthenware. He described it as “quite new in appearance, covered with rich and brilliant glaze, bearing sudden alterations of heat and cold, manufactured with ease…and consequently cheap.”

Competition amongst potters to produce whiter ceramics continued. In the mid-1770s one of Wedgwood’s rivals got ahead with a pale “china glaze”. He soon came back into the lead with a “pearl white”, now known as pearlware.

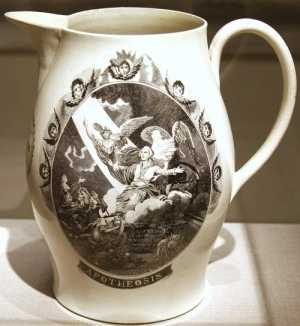

Creamware lent itself to decoration with transfer printing. This is not only cheaper than hand painting; it also allows for a very detailed surface design with elaborate drawing and lettering. Other decorative effects on creamware included piercing and embossing.

Creamware was popular for a wide range of household pottery appearing in the Georgian dining-room and on the tea-table. It brought a finer kind of tableware to middle-class families, and wasn’t only for the rich. It was also used for commemorative items, like the pitcher, or jug, in the photo. English-made for the American market, this was one of many similar exports leaving from Liverpool.

America’s own creamware production started with John Bartlam in 1770s South Carolina. By the 1790s Philadelphia was a centre for manufacturing this kind of tableware. Many of the potters described their products as queensware, or like queensware.

Wedgwood-style creamware continued to be popular until the mid-19th century. By this time the names creamware and queensware were applied to a wider range of pottery. Some of it was not at all fashionable, and was much coarser or browner than the cream ceramics produced by the innovative 18th century manufacturers.

Photos

Photographers credited in captions. Links to originals here: Wedgwood plate, teapot, American pitcher. More picture info here