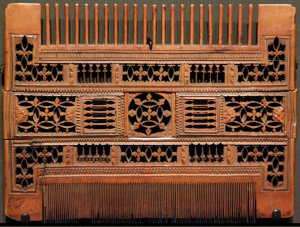

This table is a fine example of the 18th century fashion for specialised furniture designed to suit particular interests and hobbies. It’s beautifully crafted by a skilled cabinet-maker for a client with plenty of money. Look at the inlay work in the games boards, the edgings, the pairs of dice – and all over. Set in the walnut surface are maple, plum, mahogany and other woods, expertly cut and fitted together.

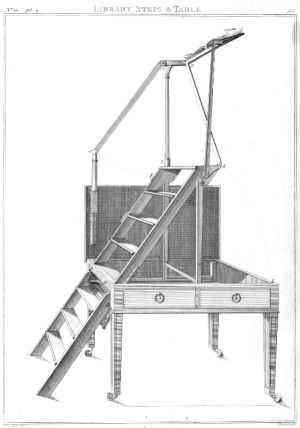

The later 1700s saw more and more furniture created exclusively for people’s leisure activities. Clever metamorphic step-chairs for private libraries, and card tables for the drawing-room are two examples I’ve already written about. Ladies’ (needle)work tables were surprisingly often combined with chess boards, and are sometimes as elaborate and decorative as the games table shown here. Stylish, ingenious pieces of furniture suited the mood of the times.

Games boards can be seen occasionally on earlier furniture, like the amazing 16th century “Eglantine” table covered with fine marquetry at Hardwick Hall, England. (Detail pictured below.) But the 18th century brought something new. The table to the right is not as fine as the one in the main picture, but it is probably more typical:

The top is inlaid as a chessboard on the under side, and is made to slide in grooves and to be reversible when required. The top when removed discloses two compartments fitted for backgammon. This game is one of considerable antiquity in England, and was generally referred to as “the tables”. Although now relegated to country vicarages and the homes of the smaller squirearchy, it was a fashionable amusement during the eighteenth century, and one at which considerable sums were won and lost by the “bucks” of the Georgian period and the days of the Regency.

Herbert Cecsinsky, English Furniture of the Eighteenth Century, 1909

Porcelain, and more table details

The bigger porcelain box on the table at the top of the page is for game tokens or counters, and was made by Meissen, probably between 1750 and 1780. The little green one is a Meissen snuff box made c1745. Inside the lid (sorry, not visible) is a scene of people playing tric-trac, a kind of backgammon. The glass beakers with playing card decoration are the oldest things in sight; they come from early 1700s Saxony.

The German table, in the Deutsches Historisches Museum, is approx. 35 by 29 inches, and 29 inches high. The English Georgian table is 28 and a half inches high. The top is only 20 by 22 inches when the side flaps are down. When up, they rest on hinged supports, and make the table’s full length 39 inches.

Photos

Photographers credited in captions. Links to originals here: Games table, Hardwick Hall table. More picture info here

//

http://pagead2.googlesyndication.com/pagead/show_ads.js