Who uses boot scrapers in the 21st century? Portable ones are on sale for gardeners, and for anyone else who wants to tackle muddy boots before approaching clean houses, cars, or paths. But the days of iron scrapers being placed at every door are over. The finest ornamental 19th century scrapers are still there beside elegant townhouses and country mansions. Scrapers have stayed on some smaller homes, especially where the scraper is embedded in the wall. Plain, functional scrapers sometimes remain by historic buildings.

Gone are the days of architects and builders planning for boot scrapers:

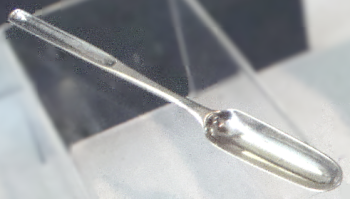

Scrapers for the feet may be let into the wall of the cottage, on each side of the door, a cavity being left over the scraper for the foot, and one under it for the dirt. There are various forms of scrapers for building into walls, which may be had of every ironmonger; and all that the cottager has to do is to choose one analogous to the style of his house. There are detached scrapers in endless variety; the most complete are those which have brushes fixed on edge, on each side of the scraper…

An encyclopædia of cottage, farm, and villa architecture and furniture …John Claudius Loudon, London, 1839

Schools no longer put scrapers on their list of essentials:

The Scraper ….. the steps or platform leading to the door ….. either will be incomplete without a strong, convenient shoe scraper at each side. Two will be required, for the reason that the pupils enter the school, morning and afternoon, about the same time, and if there be only one scraper, it will either cause delay or compel some to enter the building with soiled shoes. Cleanliness and neatness are amongst the cardinal virtues of the school-room ; and every means of inculcating and promoting them should receive the earliest and most constant attention.

JG Hodgins, The school house: its architecture, external and internal arrangements, Toronto, 1876

What we do have now are enthusiasts who just love old boot scrapers. Since these are often fixed into stone, they are best collected by photographers. One collection is mostly from the UK or US. Another is from Brussels where, says the introduction, scrapers used to be part of the etiquette and ritual for entering both public buildings and individual homes. A Toulouse “collector” has analysed local styles and named them: ram’s horns, fir-cones etc.

When did boot scrapers arrive as a normal part of daily life? The first print references start mid-18th century, when they are simply called scrapers.* I haven’t seen any that go back as far as this, but am hoping a “collector” may know of one and add a comment – please. Foot scraper and shoe scraper are terms also used, but boot scraper is far the most common name.

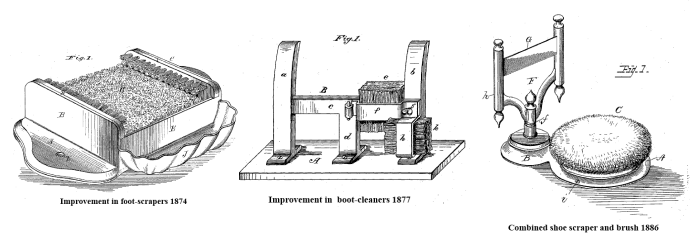

They attracted 19th century inventors with an eye on patenting newer, cleverer kinds of scraper: quite often combined with brushes. Some of these look useful, some don’t, but none has the elegance of the best architect-endorsed scrapers, chosen to suit the house they were protecting from mud. One design that stands out from the crowd is seen in New York and Savannah, Georgia. By integrating the scraper into the railings it avoids the “afterthought” look of a shoe-cleaner that doesn’t suit the architectural style of the house, but it isn’t quite as obvious as a free-standing scraper. Did visitors know where they were supposed to clean their footwear?

Specification of Works to be done in erecting and completely finishing a Villa….with all the necessary appurtenances [sic]….

Iron-founder…Provide cast-iron strong tray boot scrapers to front and back doorways.

Specification of Works required to be done in erecting and completely finishing a Pair Of Semi-detached Cottages….

Iron-founder….Fit up to each front door a neat iron knocker and a neat iron-pan scraper.

Practical specifications of works executed in architecture, civil and mechanical engineering, London, 1865

Photos

Photographers credited in captions. Links to originals here:

White boot scraper, school boot scraper, arch scraper, scraper and railings, dragon scraper.

More picture info here

Notes

*Oxford English Dictionary cites Swift’s Directions to Servants 1745