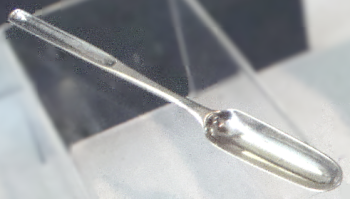

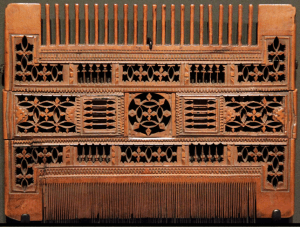

The most beautiful combs owned by ladies in late medieval and Renaissance times were highly ornamented in between their two rows of teeth. They look special, and they are. Some of the best were given as love tokens, and the fine, lacy carving included mottos, hearts, dates or initials. Did the young ladies use their admirers’ gifts? Or did the real hairdressing get done with plainer combs? The simple comb in the 17th century painting below looks easier to hold than a really gorgeous piece of carved wood.

And would you use your romantic, artistic comb for everyday hair hygiene? Apologies to anyone who is squeamish about infestation, but the fine-toothed side of the comb helped people deal with nits and lice, which people used to take more for granted than today.

H-combs

The H-shaped structure framing the teeth means that some people call these H-combs. Archaeologists call them double-sided. In Northern Europe there were double-sided H-combs in the early medieval period, while in the Middle East they go back more than 2000 years.

In late medieval Europe, especially France and Italy, beautifully decorated combs were considered a desirable gift from a knight to his lady. They could be teamed with a matching mirror and hair parter, and fitted into a dressing case (trousse de toilette), typically made of leather. Boxwood, bone and ivory were the most common materials; in all of these the teeth needed to be cut along the grain for strength. Boxwood is probably the only European wood dense enough to allow a special saw (a stadda) to cut fine teeth into the comb. These saws had two blades set close together and could cut 32 teeth to the inch or even more.† There are numerous pictures from medieval times onward showing ladies using plain H-combs, like the one from the Luttrell Psalter below right. Yet I don’t know of any showing an elaborately carved and pierced comb being used.

The most decorative combs started to become less popular as love gifts around 1600, though opinions vary on exactly when the fashion faded away. Plainer wooden H-combs were handmade up to 1900 or so. In the later 17th century there was a fashion for engraved tortoiseshell combs of this shape in the West Indies. Incised patterns with white filler, and frequent use of tulip designs, suggest combs there were influenced by Dutch craftsmanship.

†Information about the saw and other historical details come from Edward Pinto’s Treen and other wooden bygones. He casts doubt on the idea that many surviving combs were “liturgical combs” for priests to use when preparing for church rituals. Some of these were undoubtedly secular combs, made for rich people, but not for the clergy, he believes.

A lover may freely accept from her beloved these things: a handkerchief, a hair band, a circlet of gold or silver, a brooch for the breast, a mirror, a belt, a purse, a lace for clothes, a comb [pecten], sleeves, gloves, a ring, a box, a keepsake of the lover, and, to speak more generally, a lady can accept from her love whatever small gift may be useful in the care of her person, or may look charming, or may remind her of her lover, providing, however, that in accepting the gift it is clear that she is acting quite without avarice. Capellanus, De Amore, Book 2, c1180

Photos

Photographers credited in captions. Links to originals here: First comb, Other combs, More picture info here